First built in 1898, the Inner Sunset’s oldest firehouse on 10th Avenue between Irving and Judah has been occupied continuously since construction. Over the last 117 years, the building has been home to two fire companies, a school, and currently, a publishing company.

Designed by architect Charles R. Wilson, the firehouse at 1348 10th Ave. was built for Chemical Co. No. 2, an SFFD company that used chemicals for fire control. Wilson designed several other buildings in San Francisco that remain, including the Empress and Windsor hotels in the Tenderloin.

In 1900, Company No. 2 was relocated to 1819 Post St. to make room for Engine Co. No. 22, which tapped the city’s new water mains. (By 1948, all SFFD chemical companies were converted into Tank Wagon Companies.)

The exterior still has all the hallmarks of a classic firehouse (including a tower where hoses hung to dry) but once inside, it’s clear that the space has been adapted for different uses over the last century. The city moved Engine Co. No. 22 out in 1962 and sold the building in 1969 to Oakes Children’s Center, a school for children with “a range of behavioral and neurological disorders.” In 1970, the firehouse was listed as #29 out of 265 designated San Francisco landmarks.

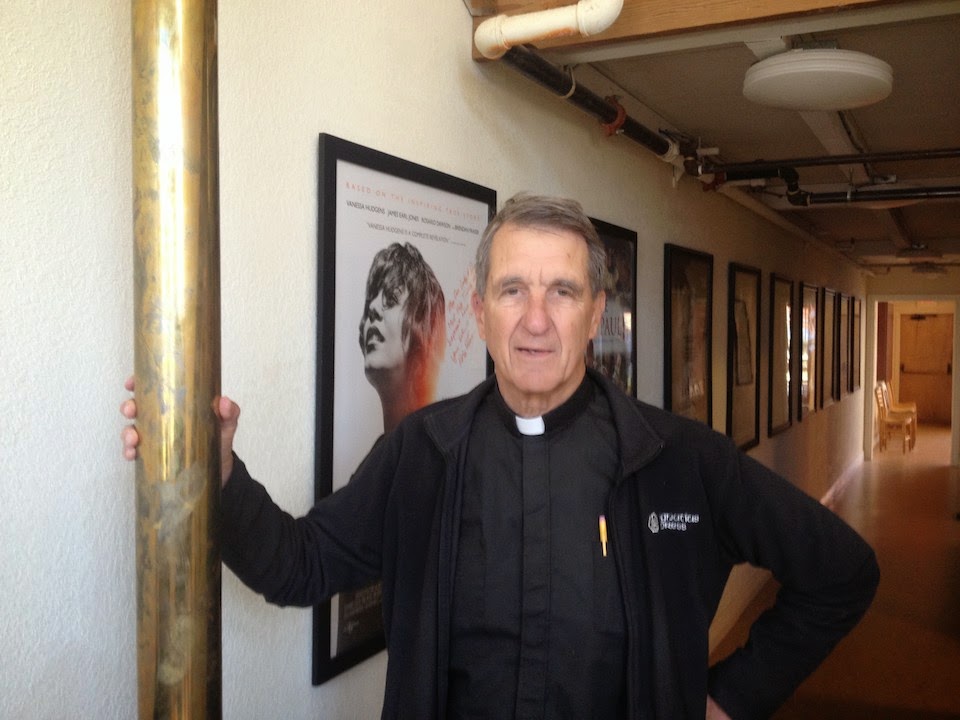

By 2008, the school had outgrown the space and sold the building to Ignatius Press, a Catholic publishing company. For Father Joseph Fessio, an editor, “there’s no place in the entire world that’s as convenient as this location. It’s like having a little town in the middle of a big city.”

Before relocating to the firehouse, Ignatius Press was operated from a house near USF that was owned by Carmelite nuns. Today, about 15 people work out of the converted space. “We didn’t want to get an industrial building, because we’re more a family than a business,” said Fessio.

After it moved in, Ignatius Press significantly remodeled, adding a mezzanine level and refurbishing the basement with an exercise room and a guest room.

“This building was perfect—it was zoned so we could have a school, it’s in a residential neighborhood near the stores, and the N-Judah is right there,” said Fessio. “This area has everything.”